Earning Money by Investing Without Risk: Is It Possible?

Let’s talk about it…

Investing our savings, watching them grow over time and protecting them from inflation without risking any loss is everyone’s dream.

Unfortunately, one of the few certainties in the financial world is that there is no return without risk: if we want our savings to grow, we must accept a greater or lesser chance of losing them. What we can do, at best, is settle for relatively modest returns and minimise the risks.

Let’s see how: take, for example, an investment in bonds.

Although the name might sound intimidating, bonds are one of the simplest forms of investment. By buying them, we are essentially lending money to the issuer – for instance, a country (as in the case of government bonds) or a private company.

As the name suggests, the issuer – the entity that borrowed the money by issuing the bond – is legally bound to repay us at maturity, in the case of standard bonds, a fixed amount called the face value, plus interest calculated as a percentage of that nominal value.

Example:

If the bond’s face value is €100 and the promised annual interest rate is 3%, after one year we would be entitled to receive €3 in interest plus the €100 repayment.

But what if the issuer cannot pay us back?

In that case, we can only hope to recover part of the bond’s face value. By purchasing any bond, we are exposed to what finance calls credit risk – the risk that the borrower cannot repay us.

If we want to minimise risks (and returns), the first step is to look for reliable issuers with a low risk of default – for example, companies with solid assets, low debt, and stable revenues and costs.

The second factor to consider is the bond’s maturity: the further away the repayment date, the greater the chance that adverse events occur and the issuer defaults. The future is uncertain, and accidents can happen. Therefore, for issuers with the same level of reliability, shorter maturities usually mean lower credit risk (and lower returns). Furthermore, when the bond has a fixed rate, a long maturity exposes us to the risk of unexpected interest rate increases, which could make us miss out on better opportunities and even incur losses if we have already invested.

What is the least risky bond investment?

In developed countries, the most reliable issuer is usually the government, because the likelihood of a government default is generally lower than that of any company operating within its borders.

Lending money to the government for a short period is therefore typically the least risky form of investment within a country, and the return we earn is called the risk-free rate.

But don’t be misled by the term: truly risk-free returns do not exist. The concept of a risk-free rate is largely theoretical (in practice, a “true” risk-free rate does not exist).

And if we aim for higher returns (and higher risks)?

The (almost) risk-free rate plays a key role in finance because it serves as the starting point for assessing and comparing risks and returns and for pricing all financial instruments. Specifically, the higher the risk of an instrument, the greater the extra return investors will demand over the risk-free rate.

This makes sense: why should we invest in risky assets if we can invest in an (almost) risk-free one? Only the promise of an extra return could persuade us!

This extra return is called the spread, and it increases with risk.

Let’s clarify with an example.

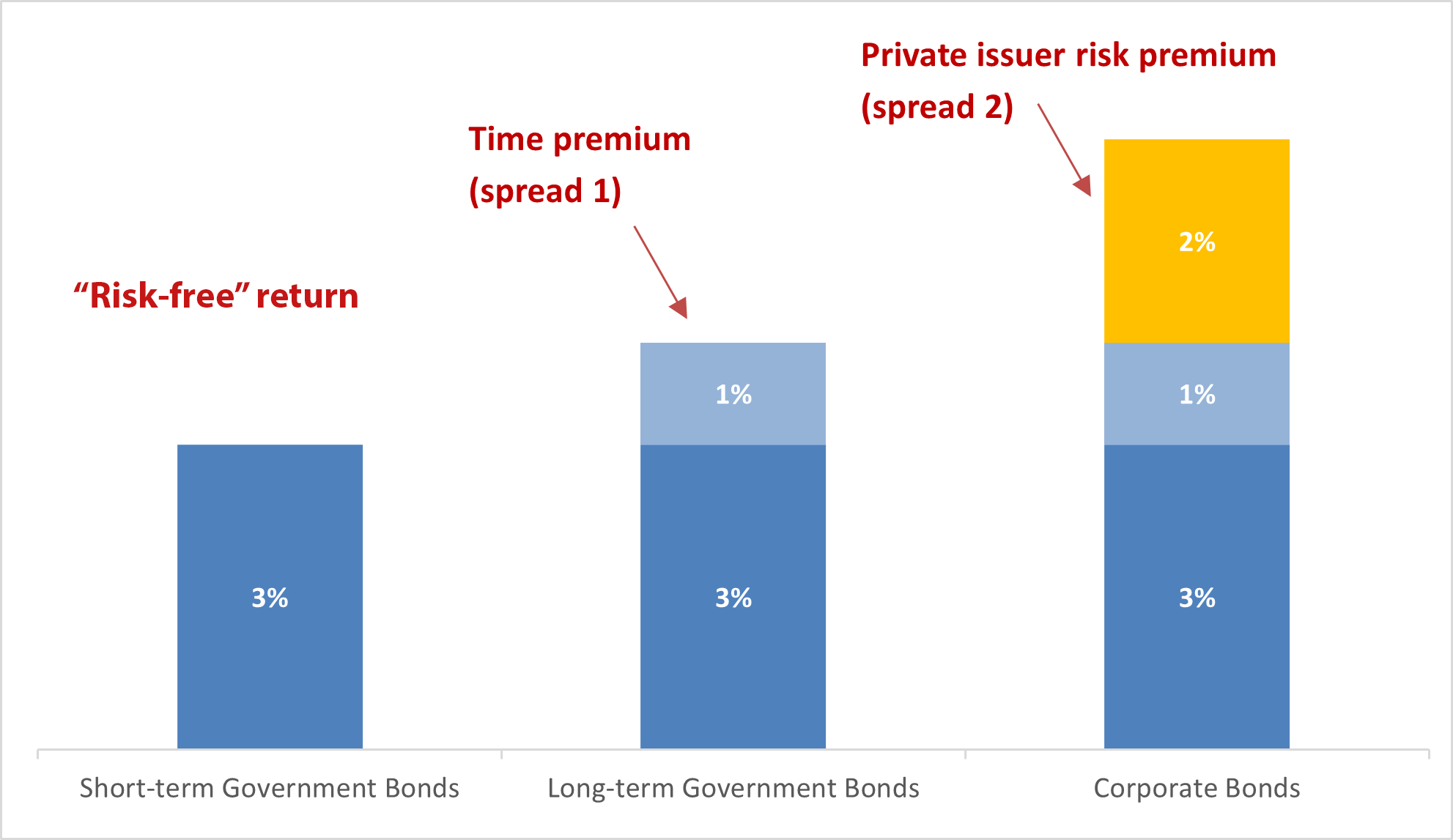

Suppose the risk-free rate – the rate paid by a short-term government security (government bond) – is 3% per year. If we invest €100 with minimal risk, after one year we would receive €103: €3 in interest plus €100 in principal.

If we invest in long-term fixed-rate government bonds, accepting a higher risk, we would want something extra, say 4%. The difference between the two returns – 1% – is the spread, the premium that compensates us for the additional risk.

If we want even higher returns, we could buy corporate bonds – those issued by private companies. These companies are generally less reliable than the State, and the probability of losing our money is higher. For this reason, we would not settle for 4% but would demand, for example, 6%. The difference – 2% – is the spread between long-term government bonds and corporate bonds, compensating us for the greater risk of issuer default.

We can think of the return on a financial instrument as a pyramid made up of building blocks stacked on top of each other. The first block is the risk-free rate (in our example, 3%) – the return we can earn by taking negligible risk. The other blocks represent the extra return we demand for taking on more risk (for long-term government bonds, the second block is 1%; for corporate bonds, the third block is 2%). The more blocks and the thicker they are, the higher the return we earn in exchange for greater risk.

In conclusion, remember that investing without taking any risk is impossible. Even with the risk-free rate, however small, some degree of risk always exists. And if we want higher returns, we must always bear in mind that we are taking on higher risks.

So, be wary of anyone offering very high returns at low risk – they simply do not exist!

Youtube

Youtube

X - Banca d’Italia

X - Banca d’Italia

Linkedin

Linkedin

RSS

RSS